報告真本藏大英圖書館,可透過 Gale 數據庫存取

報告附地圖 1 -

報告附地圖 2 -

2590

L/MIL/17/20/3/1

"The information given in this Document is not to be communicated, either directly or indirectly, to the Press or to any person. not holding an official position in His Majesty's Service.

DRO11

205-21-Al

INDIA OFFICE.

MILITARY REPORT

HONG

ON

KONG

VOLUME I. (GENERAL INFORMATION)

General Staff, The War Office`

1930

LONDON

Printed under the authority of HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE by HARRISON AND SONS, LTD., Printers in Ordinary to His Majesty,

44-47, St. Martin's Lane, London, W.C.2.

10R:L/mic/17/20/3/1

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY.

THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF H.B.M, GOVERNMENT.

NOTE,

The information given in this Document is not to be communicated, either directly or indirectly, to the Press or to any person not holding an official position in His Majesty's Service.

DIEU

PROIT

MILITARY REPORT

ON

HONG KONG

VOLUME I. (GENERAL INFORMATION)

General Staff, The War Office

1930

LONDON:

Printed under the authority of HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE by HARRISON AND Sons, LTD., Printers in Ordinary to His Majesty, 44-47, St. Martin's Lane, London, W.C.2.

This report has been prepared by the General Staff at Hong Kong from the latest information available. It is requested that any errors, omissions, or changes in conditions may be brought to the notice of the Director of Military Operations and Intelligence, The War Office.

Acknowledgment is due to the following for permission to include extracts from their publications:

THE CHINA YEAR BOOK, edited by H. G. W. Woodhead,

C.B.E., published by the Tientsin Press Ltd.

THINGS CHINESE, by J. Dyer Hall. Published by

John Murray.

THE RESHAPING OF THE FAR EAST, by B. L. Putnam

Weale. Published by Macmillan & Co., Ltd.

J. R. E. CHARLES,

Major-General,

Director of Military Operations

and Intelligence.

THE WAR OFFICE,

1st February, 1930.

3.

LIST OF CONTENTS.

Contents.

CHAPTER I.-HISTORY

1. Events leading up to the occupation of Hong Kong by the British; treaties ceding the Island of Hong Kong and the Kowloon Peninsula to Great Britain; treaty leasing the "New Territory to Great Britain; occupation of the New Territory..

2. Military operations in the Colony

"

3. List of books of reference dealing with the History of

Hong Kong

•

CHAPTER II.-SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT

1. General description

2. Central Government

3. Local Government

4. Legal system

5. Finance

..

•

CHAPTER III.-POPULATION

1. Races; their distribution, numbers, characteristics,

physique and military value

2. Religions

3. Languages; interpreters

4. Education

5. Labour available in different districts; normal wages; how best obtained and organized; availability outside its own district; types of tools used

•

6. Attitude of races towards each other, and to Europeans

and foreigners

7. Normal diet

8. Foreign residents

CHAPTER IV.-POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY

1. General description and area of the Colony

2. Frontiers of Ceded and New Territory

(B 307/177)x

PAGE

6:

10

10

11

11

12

12

12

14

18

21

24

25

26

27

28

28

29

29

A 2

Contents.

4

3. Principal towns

CHAPTER IV.-continued.

(a) Population

(b) Types of houses and streets; billeting facilities (c) Municipal system

(d) Principal government buildings; ; foreign con-

sulates

(e) Hospitals

(f) Banks..

(g) Factories and engineering works

(h) Power stations

(i) Tramways

(j) Water supply .

(k) Sanitation

..

(1) Supplies; whence drawn

4. Description of port

(a) Control of the port

(b) Landing facilities

(c) Labour supply

(d) Cargo handling appliances

(e) Transit accommodation

•

+

•

PAGE

29

29

30

30

30

•

•

31

32

32

32

32

32

32

32

•

•

33

33

33

..

33

33

@ www. w ca

33

33

33

33

34

(f) Road and rail communications

• •

• •

•

• •

•

•

(g) Average amount of coal and other fuel usually in

stock; ownership..

(h) Situation and location of oil tanks..

(i) Details of dockyard and accommodation

(k) Possible aerodromes and aeroplane bases or

anchorages

5. Anchorages and landing places, other than ports. General

remarks

38

38

CHAPTER V.-PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY

1. Geological formation of country

39

2. Mountains

39

3. Rivers

40

4. Woods and forests

40

5. Marshes and swamps

6. Water supply

41

• •

41

CHAPTER VI-CLIMATE

1. Nature of climate

2. Effect on Europeans

3. Effect on natives

4. Health

•

5. Effect on animals

•

•

6. Effect on facility of movement

7. Temperature (maximum and minimum)

42

42

43

43

44

44

45

5

CHAPTER VI.-continued.

8. Seasons and rainfall

9. Prevalent winds and hurricanes

10. Earthquakes

11. Magnetic variation

Contents.

12. Prevalent diseases and precautions to be taken against

them

13. Clothing suitable for various seasons

14. Insects

•

1. Roads

CHAPTER VII. COMMUNICATIONS

2 Navigable waterways

3. Railways

4. Telegraphs, telephones and postal

1. Crops

CHAPTER VIII.-RESOURCES

PAGE

45

46

47

47

47

50

50

53

53

54

..

56

2. Cattle

3. Dairy produce

4. Transport

5. Minerals

6. Timber

7. Commerce

•

•

8. Shipping; ocean and coastwise

1. General

CHAPTER IX.-ARMED FORCES

2. Regular troops

•

3. Local forces

4. Police force

•

•

酆

59

59

•

59

59

60

•

60

60

61

··

•

•

8888

63

63

68

69

CHAPTER X.-AVIATION

1. Aerodromes and landing grounds

2. Meteorological conditions

3. Local fuel resources

70

70

• •

72

222

APPENDICES

APPENDIX I.-(a) Weights and measures

22

(b) Currency

II. Treaties between Great Britain and China

MAPS

Hong Kong & in. to 1 mile. (G.S.G.S. No, 1393B) Cables and air lines. (O.R. 441)

73

73 75

IN POCKET.

}}

Chap. I.-History.

CHAPTER I.

6

HISTORY

1. Hong Kong is a Crown Colony, the history of which begins with its cession to Great Britain in January, 1841. This cession was confirmed by the Treaty of Nanking, dated 29th August, 1842.*

The Charter of the Colony is dated 5th April, 1843.

In the troubles which preceded the first war with China, the necessity for having some place on the coast whence British trade might be protected and controlled, and where officials and merchants might be free from the humiliating requirements of the Chinese authorities, became so evident that, as early as 1834, Lord Napier urged the Home Govern- ment to send a force from India to support the dignity of his commission. A little armament," he wrote, should enter the China seas with the first of the south-west monsoons, and on arriving should take possession of the island of Hong Kong, in the Eastern entrance of the Canton River, which is admir- ably suited for the purpose." Two years later Sir George Robinson, endorsing the opinion of Lord Napier,

"that nothing but force could better the British position in China,” advised the occupation of one of the islands in this neigh- bourhood, singularly adapted by nature in every respect for commercial purposes.

In the early part of 1839, affairs approached a crisis, and, on 22nd March, Captain Elliot, the Chief Superintendent of Trade, required that all the ships of Her Majesty's subjects at the outer anchorages of Canton should proceed forthwith to Hong Kong, and, hoisting their national colours, be prepared to resist every act of aggression on the part of the Chinese Government. When, in accordance with this decision, the British community left Canton, the Portuguese Settlement of Macao afforded them a temporary refuge, but their presence there was made the occasion by the Chinese Government of threatening demonstrations against the Settlement. In a despatch dated 6th May, 1839, Captain Elliot wrote to Lord Palmerston : "The safety of Macao is, in point of fact, an

* See Appendix II.

7

Chap. I.-History.

object of secondary importance to the Portuguese Govern- ment, but to that of Her Majesty it may be said to be an indispensable necessity, and more particularly at this moment," and he urged upon his Lordship "the strong necessity of concluding some immediate arrangement with the Governor of His Most Faithful Majesty, either for the cession of Portuguese rights at Macao or for the effectual defence of the place and its appropriation to British uses by means of a subsidiary Convention.' Happily for the permanent interests of British trade in China, this suggestion came to nought, and Great Britain found a much superior lodgment at Hong Kong.

:

The measures instituted by the Chinese in reference to Macao decided Captain Elliot that a longer stay there would compromise the safety of that settlement, and accordingly he embarked for Hong Kong on 24th August, 1839, accom- panied by the officers of his establishment, hoping that his own departure might satisfy the Chinese, but when it became evident that they intended to expel all the English from Macao, the whole British community was embarked on the following day, and under escort of H.M.S. "Volage," arrived safely at Hong Kong. At that time there was, of course, no town, and the community had to reside on board ship. The Chinese at first tried to stop all supplies reaching the British, and this led to a miniature naval battle in Kowloon Bay between the cutter "Louise," accompanied by the " Pearl," a small armed vessel, and the pinnace of H.M.S. Volage," against three large men-of-war junks, whose presence had prevented the regular supplies of food. The junks were worsted, and trade was restored for a few weeks, but, the Chinese again becoming aggressive, a naval action took place off Cheun Pee, when the Chinese retired in great distress. After this battle, and in spite of the remonstrances of the British mercantile firms, Captain Elliot decided to remove the British shipping to Kong Too, and it was not until January, 1840, that a British expedition arrived and Hong Kong became the headquarters of Her Majesty's forces.

At first the progress of the Colony was very rapid, and roads and buildings were constructed in the city of Victoria. In 1844 the prevalence of malaria led to recommendations to abandon the Colony, but these were overruled by the governor, Sir John Davis.

In 1860, while Sir Hercules Robinson was governor, the peninsula of Kowloon* was placed under British control by

*This name frequently appears on maps, and in most early writings as Kau-Lung," but the more modern form of "Kowloon" appears now to be that generally accepted. The Chinese characters signify" nine dragons."

Chap. I.-History.

8

a treaty dated 24th October of that year, extracts from which are given in Appendix II, and shortly afterwards became a great camp, the British and French troops of the allied expe- ditionary force to North China being for some time quartered there.

Large local banking, dock, steamboat, and insurance companies were established between the years 1865 and 1872, and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 considerably increased the trade of the place.

The Colony steadily progressed, though naturally with some fluctuations in prosperity, until 1889, after which date a period of deep depression, arising partly from fluctuations of exchange, partly from over-speculation and partly from other causes, was experienced, and continued for five years.

2

In 1898 an agreement was entered into whereby China ceded the "New Territory to Great Britain on a 99 years' lease from the 1st July in that year. A copy of the agreement is given in Appendix II.

The reasons for this agreement were, firstly, because it had long been recognized that the safety of the Colony would be seriously jeopardized in the event of a foreign power obtaining the lease of Mirs Bay and the adjacent foreshore, which, lying some 25 to 30 miles north and north-east of Hong Kong, affords a commodious and safe anchorage in deep water no matter what wind is blowing; and, secondly, the possession of the range of hills and the passes leading over them from Mirs Bay towards Kowloon was an essential factor in the defence of the island from an attack from the mainland, for the reason that hostile guns mounted on these hills would command the harbour and town and would even take some of the batteries in reverse. Reference to the Treaty, which was signed at Peking on the 9th June, 1898, shows that it is expressly stipulated that the waters of Mirs Bay shall be British, although a clause is added to the effect that Chinese men-of-war, whether neutral or otherwise, shall retain the use of these waters.

The ceremony of formally taking over the territory was fixed for the 17th April, 1899, when the flag was to have been hoisted at Tai-po-hu, the present headquarters of the adminis- tration, and the day was proclaimed a general holiday.

The inhabitants of the New Territory, however, resented the cession to Great Britain and attacked the parties engaged on the preliminary arrangements, burned matsheds which had been erected for occupation by the police, and gave other evidence of organized opposition, so that it was deemed advisable to commence full jurisdiction on 16th April, on which date the flag was hoisted. In the convention it was

9

Chap. I.-History.

provided that Kowloon City* was to remain Chinese, but the action of the Chinese authorities on the above occasion having been open to distrust, it was decided to seize Kowloon City and Sham-chun; this was accordingly done on the 16th May, 1899, without opposition.

Sham-chun, an important town on the river of the same name just beyond the boundary originally agreed upon, was restored to the Chinese authorities in November of the same year. From 1899 to the present day the Colony has made rapid progress, and Hong Kong now ranks as one of the most important commercial ports in the world.

Though this progress has not been checked by any events involving the use of armed force, it has been interrupted, on more than one occasion, by political and economic disputes which have arisen with the neighbouring Chinese province of Kwangtung. The most important of these disputes were the seamen's strike of 1922 and the general strike and boycott of 1925. The former, though based originally on economic grounds, was exploited and aggravated for political purposes. After lasting for several months and causing great losses, it was settled by economic adjustments.

The settlement of the 1922 strike was, not unnaturally, held by the Chinese to constitute a political victory for Canton, and is considered to have been a contributory cause of the more serious strike and boycott which began in June, 1925, and which were not settled till November, 1925, and end of 1926, respectively.

This dispute, which is one manifestation of the wave of unrest which passed over China in 1925, had no clearly defined basis. The general strike, with which it started, was instituted to bring political pressure to bear on Great Britain.

For a few days great inconvenience resulted, and if, during this time, an external or internal threat to the peace of the Colony had arisen, the action of government forces for the maintenance of order would have been much embarrassed. No such threat arose, however, though whether this was due to the precautions taken and a display of force which was shown, or to other causes, cannot be stated, and in a few weeks the strikers were largely replaced or returned to work. The boycott, however, continued, and was enforced, and caused much loss to commerce, up to the end of 1926.

2. The only occasions on which it has been necessary to employ

* The modern town of Kowloon has been developed at the southern end of the Tsim-sha-tsui peninsula. The old Chinese town of Kowloon lies about three miles to the N.N.E. It is generally known as Kowloon (old) City. Though developments have taken place in the near neighbourhood, the old city remains much as it was in the days of the Chinese occupation.

Chap. I.-History.

"

10

was

troops in Hong Kong were when the New Territory taken over in 1899 and on other occasions to guard the frontier against possible incursions by Chinese soldiery.

On the former occasion a force of some 2,500 Chinese troops assembled near Sheung-tsun, was dispersed without difficulty or loss to British troops; on the latter, small detachments of troops have been sent to reinforce the police, and have succeeded, with the use of but little force, in preventing any organized incursions being made into British territory.

It may, in fact, be said that hitherto the Chinese, whether inside or outside Hong Kong, have never, since 1899, shown the slightest desire to come into physical conflict with British authority in Hong Kong.

3. The following books concerning Hong Kong can be obtained by purchase :-

(a) "Europe in China." The history of Hong Kong from the beginning to the year 1882, by E. J. EITEL. (Published by Luzac & Co., London, and Kelly & Walsh, Hong Kong.)

"

(b) Annual Administrative Reports of Hong Kong." (Published by the Hong Kong Government. Obtainable from Colonial Secretary,

Kong.)

Hong

(c) "The China Year Book." (Published by The Tientsin Press, Limited, 181, Victoria Road, Tientsin. Obtainable at all booksellers in the Far East, and from Messrs. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., London.)

(d)

(e)

"

The Directory and Chronicle of China, Japan, &c." (Published by "The Hong Kong Daily Press, Limited," 1, Chater Road, Hong Kong, and 131, Fleet Street, London, E.C.4.)

The China Review.' (Published by Messrs. Kelly & Walsh, London and Shanghai.)

Volume XX contains much of interest concern- ing Hong Kong. It is out of print, but can be found in reference libraries.

(f) Colonial Reports-Annual--Hong Kong. Published by H.M. Stationery Office, Kingsway, London, W.C.2, or through any bookseller.

(g) "The Restless Pacific." By Nicholas Rooseveldt. Published by Scribeners, New York. Obtain- able from Scribeners, 168, Regent Street, Lon- don.

(h) Practically every book dealing with any Far Eastern question devotes considerable attention to Hong Kong.

11

Chap. II.-General Description.

CHAPTER II.

SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT

1. General Description

The Government is administered by a governor, who is also commander-in-chief, aided by an executive council of six official and three unofficial members.

The Legislative Council is presided over by the Governor, and is composed of the General Officer Commanding the Troops, the Colonial Secretary, the Attorney-General, the Treasurer, three other official members appointed by the Governor- usually the Secretary for Chinese Affairs, the Director of Public Works and the Captain Superintendent of Police--and six unofficial members, one of whom is elected by the Chamber of Commerce and another by the Justices of the Peace. The remaining four, two of whom are of Chinese race but British nationality, are nominated by the Governor. The unofficial members are appointed for a period of four years.

Demands for a greater measure of popular representation were made by the British residents to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1916, 1919, and 1922, but without success.

2. Central Government

The following is a list of the Civil departments of the Central Government :—

Audit Department. Attorney-General's Depart-

ment.

Botanical and Forestry De-

partment.

Colonial Secretary's Depart-

ment.

Crown Solicitors' Depart-

ment.

District Officers. Education. Governor.

Harbour Master's Depart-

ment.

Imports and Exports De-

partment.

Kowloon-Canton Railway,

British Section:

Land Office.

Magistracy, Victoria. Magistracy, Kowloon. Medical Department. Official Receiver's Office. Police Department and Fire

Brigade.

Post Office.

Prison Department.

Public Works Department. Royal Observatory. Sanitary Department. Secretariat for Chinese

Affairs,

Supreme Court, including the Courts of two Judges, the Registry, and the Official Receiver's Office. Treasury.

Volunteer Defence Corps.

Chap. II.-Municipal and Local Boards.

12

3. The following is a list of all Municipal and Local Boards, with particulars of their duties and membership :-

Licensing Board-

To consider applica- 2 official members, 5 mem-

tions for the grant or

transfer

licenses.

Medical Board-

of liquor

To consider applica- 7 tions for the regis- tration of medical and surgical practi- tioners.

Sanitary Board-

To make, and when

necessary

to alter, amend or revoke, sanitary bye-laws and to consider other matters in relation to public health and sanitation.

4. Legal Systems

bers appointed by the Governor.

members appointed by

the Governor.

8 members appointed by

the Governor.

2 members elected by special and common jurors.

The "Colonial Courts of Admiralty Act, 1890," regulates the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in Admiralty cases.

English common and statute law, as amended by Colonial ordinances, forms the basis of the legal system.

The Law as to civil procedure was codified by Ordinance Number 6 of 1901.

5. Finance

Details of revenue and expenditure are contained in the China Year Book and Hong Kong Blue Book.

The Colony has a small public debt. A loan of £200,000 was contracted in 1886. Another loan of £200,000 was con- tracted in 1893, and in 1894 the unredeemed balance of the first loan was converted from 4 per cent. debentures into 34 per cent. inscribed stock, thus bringing it into uniformity with the loan raised in 1893. In 1906 the Government raised a loan of £1,100,000 in London at an average price of £99 1s. Od. per cent., bearing interest at the rate of 3 per cent. This money was originally lent to the Chinese Government for the purpose of redeeming the Canton-Hankow Railway conces-

13

Chap. II.-Finance.

sions from the various persons who had acquired interests in it from the original American concessionnaires. The total cost of the loan, including expenses of issue, was £1,143,933. It has now been fully expended on railway construction within the Colony and the loan has been fully repaid.

A sum of $5,000,000 was presented in 1916 and 1917 to His Majesty's Government for war purposes, three out of the five million dollars thus voted being raised by a local loan in the former year. In 1918 a sum of £550,000 was given for the same object, while the special assessment produced $504,984 in 1917, and $1,052,760 in 1918, all of which was paid over to the Imperial authorities. At the end of 1924 the amount of the consolidated loan stood at £1,485,733, against which there was at credit of the sinking fund £467,272. Against the local loan of $3,000,000 there were the sums of $1,458,182, and £103,455 at credit of the sinking fund. The rateable value of the whole Colony in 1924-25 was $22,147,951, showing an increase of 5.16 per cent. over the previous year. The rateable value of the Colony shows an increase of 55·02 per cent in the past ten years.

Chap. III.-Races.

CHAPTER III.

14

POPULATION

1. Races; their distribution, numbers, characteristics,

physique and military value

A census taken in 1921 showed the total population of the Colony to be 625,166, but the census officers estimated that, for various reasons, the normal population was greater than that by 30,000. The smaller total, however, gave an increase of 168,427, or 36.87 per cent., on the figures for 1911-" the greatest relative increase ever recorded for the Colony." The bulk of the increase took place in the city of Victoria and Kowloon. On the island of Hong Kong there were 347,041, on the Kowloon Peninsula 123,448, in the New Territories 83,163 (i.e., 66,114 in the Northern District and 17,049 in the Southern District), and afloat 71,154. Of the boat population 38,510 were in Victoria Harbour.

The non-Chinese population was composed of 32 different nationalities, of which the following were the principal in point of numbers :-

British (4706 males and 3183 females).

Portuguese

Japanese

Americans

Filipinos

French

Dutch

Danish

Italian

Spanish

Russian

•

•

*

·

U

7889 2057

1585

470

232

• •

•

•

208

104

•

36

56

•

59

•

36

Twenty-one of the component parts of the British Empire were represented in the British inhabitants, of whom it was estimated that about 4,500 were of European race; the balance of 3,389 is made up of Chinese, Eurasian, Indian and other non-European British subjects.

The above census figures do not include the Navy or the Regular Army.

For latest figures see Hong Kong Blue Book, issued annually.

15

Chap. III.-Races.

It will be seen that a large proportion of the non-British and non-Chinese population consists of Portuguese, who are loyal and prosperous and are on the whole of good physique. There is a great distinction between the Portuguese and other Europeans. The Portuguese of Hong Kong form a European community settled in the Tropics, thoroughly acclimatized, and apparently not recruited to any extent from Europe. In one sense, therefore, they are indigenous; but in another, alien, as they retain their allegiance to their own country, and their connection with the Portuguese colony of Macao.

The Chinese largely outnumber any other race, and under British rule are, generally, well conducted. About one-third of them are British subjects by birth. They are drawn chiefly from the neighbouring maritime province of Kuang-Tung, and may be classified under the following heads :-

(a) PUN-TEI, or native Cantonese. The Cantonese form a highly reputable section of the Chinese popula- tion; they include most of the better class merchants, artisans, servants and labourers. They have frequently proved themselves useful members of the community. Most of the Tan-ka, or boat people, of whom many thousands spend their lives on junks and sampans in Hong Kong harbour, are of the Pun-tei race. (b) HAK-KA. These people, as their name signifies in Chinese, are strangers." Coming originally from the north, they have formed large settlements in various parts of China, especially in the neigh- bourhood of Wai-chow. They are a simple people, pig-headed and often careless about the truth. They supply the barbers, stonecutters, and gardeners of the Colony.

"

(c) HOKLOS, from the neighbourhood of Chin-chow and Swatow. The carriers of the "chairs and pullers of rickshas, which are still extensively used, are drawn from this race.

The Chinese urban population (mostly Pun-tei) has been attracted to Hong Kong by opportunities of business and appreciation of its security, not, in the main, as to a home, but as a miner to his camp; to a place where gold is to be won for enjoyment elsewhere. The average urban Chinese never regards Hong Kong in any other light. He usually returns to his village at least once a year, and, if he dies in Hong Kong, his body is sent home for burial. This does not, however, prevent him from establishing domestic ties in Hong Kong, but the proportion of children to adults is less than it is in

Chap. III.--Races.

16

the case of his compatriots of the rural and boat populations. The rural population of the New Territory is mainly engaged in agriculture and fishing, and is, as a rule, orderly and well behaved.

The Chinese are well built and proportioned, but short in stature, especially in the south, where it is an exception to see a man of six feet in height, the average being five feet four Both sexes inches for adult males and five feet for women. are capable of heavy manual labour, and are unaffected by extremes of climate.

In Kuang-tung Province the Chinese have assimilated the original inhabitants, whose features are now perpetuated in the faces of nominal Chinese. The skinny necks, the simian mouths, and the out-turned feet are marks which can be readily recognized.

It is impossible to define the characteristics of a people who, to a Western observer, display so many contradictory elements "" The of character. Thus Mr. Henry Norman, in his book, Far East," written before medical science was so far advanced, describes the Chinaman and the mosquito as being two great mysteries of creation, while no two writers agree in their descriptions of the predominant traits observed. Any reader, therefore, who wishes to get some insight into Chinese idiosyn- crasies would do well to study the many books devoted to the subject.

(6

The following extracts, as quoted on pages 141-166 of Things Chinese," from Sir Walter Medhurst's writings on the subject of the Chinese people, furnish, perhaps, the most apt description of the particular characteristics of those dwelling within the Colony :-

The Chinese are good agriculturists, mechanics, labourers, and sailors, and they possess all the intelligence, delicacy of touch, and unwearying patience which are necessary to render them first-rate machinists and manufacturers. They are, moreover, docile, sober, thrifty, industrious, self-denying, enduring, and peace-loving to a degree. They are equal to any climate, be it hot or frigid, and all that is needed is teach- ing and guiding, combined with capital and enterprise, to convert them into the most efficient workmen to be found on the face of the earth. John Chinaman is a most temperate They are a sociable people among themselves, and their courtesies are of a most laboured and punctilious character.

The Chinese are essentially a reading people. The Chinese have not, it is true, that delicate percep- tion of what the claims of truth and good faith demand, which is so highly esteemed among Westerners, but they know and prize both characteristics, and practical illustrations thereof

creature.

•

•

•

•

•

17

•

Chap. III.-Races.

are constantly observable in their relations one with the other and with foreigners.

Honesty is by no means à rare virtue with the Chinese.

Both kindness and cruelty, gentleness and ferocity, have each its place in the Chinese character, and the sway which either emotion has upon their minds depends very much upon the associations by which they are for the moment surrounded. When in their own quiet homes, pursuing undisturbed the vocations to which they have been accustomed, there are no more harmless, well- intentioned, and orderly people. They actually appear to maintain order as if by common consent, independent of all surveillance or interference on the part of the Executive, but let them be brought into contact with bloodshed or rapine, or let them be aroused by oppression or fanaticism, and all that is evil in their disposition will at once assert itself, inciting them to the most fiendish and atrocious acts of which human nature has been found capable."

The law-abiding qualities of the Chinese are accounted for if it is realized that in China the unit is not the individual but the family, and a family thus becomes responsible for the good behaviour of its members, while the greatest respect is shown to the "elders." This system of mutual respon- sibility among all classes acts innately as a great deterrent from serious crime and defalcations. But it is obviously not a system which can be enforced by the government of the Colony, which applies towards the Chinese the Western methods of holding the individual responsible. Conse- quently, individualism is showing itself more and more at the open ports, and is breaking up slowly, but irresistibly, collectivism and the family system.

The ignorance of the laws of hygiene, which characterizes all Chinese, and their apparent contempt for those laws even when understood by them, are well known, and even under the strict supervision which is exercised by the sanitary authorities throughout the Colony, these characteristics are a standing menace to the health of the European community. To a foreign observer it is a matter of surprise why the various diseases which this ignorance and defiance of natural laws invite, do not exterminate the Chinese altogether. While vast numbers of people do die every year of diseases entirely preventable, the fact that the number of such persons is not infinitely greater, argues, on the part of the Chinese, a marvel- lous capacity to resist disease and to recover from it. The readiness of the Chinese to throw away their lives on very slight provocation is a characteristic as marked as the tenacity of their hold upon them.

As regards the inhabitants of Southern China, Mr. Putnam

(B307/177)x

Chap. III. Religions.

18

Weale, in his book, The Reshaping of the Far East,” says: "Southern China does not contain much of the true Chinaman. It has mixed so many peoples in its pot that the vices of the half-caste and quarter-caste are uppermost, and superstition holds sway with a strength it does not possess elsewhere. The southern coast is, moreover, the old pirate coast, which the Manchus have never properly comprehended. It is the land of stinkpots and dastardly attacks on sailing ships in former days."

The military value of the Chinese inhabitants of Hong Kong and South China is very low indeed. Why this should be so it is difficult to explain, since they possess so many of the characteristics which go to make a good soldier. At times and under certain conditions they can be as brave as any; under other conditions none are more cowardly. Some privations and physical exertions they will endure with unequalled patience; others, to European eyes far less trying, will overcome them. They are wonderfully patient and intelligent as a rule, and, as a corollary to this, can show great obstinacy and stupidity.

But whatever their individual military characteristics may be, few will dispute that they have hitherto shown themselves almost worthless as combatant soldiers.

2. Religions

The following remarks (extracted from the China Year Book") on religions in China, are applicable, generally, to Hong Kong.

It is customary to speak of the religions of China as three in number-Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. Probably a more correct statement of the facts would be that China, apart from the monastical profession of Buddhism, merely recognizes one religion based on a belief in the animation of the universe with good and evil spirits, which finds expression, as one writer has said, in countless acts of propitiation or exorcism, all designed to preserve or restore the proper balance of power between good and evil," and that in this religion are included (1) ancestor worship, the very core of the religions and social life of the people; (2) Confucianism-a moral code rather than a form of worship; (3) Taoism; and (4) Buddhism, the last two supplying the forms of ritual or outward observ- ance without calling for any corresponding degree of religious faith.

Ancestor-worship enters into the life of the Chinese as a religion in a more real form than any other system. The spirits of ancestors are worshipped, and attempts to merit their goodwill and kindly offices are made more conscien-

19

Chap. III.-Religions.

tiously than in the dealings with the numerous deities incor- porated with Taoism and Buddhism. The worship of ancestors is a natural corollary to Confucianism, though antecedent to it.

an

CONFUCIANISM.-The teaching of Confucius was less original philosophy than an attempt to inculcate a standard of morality based on his interpretation of history as he had read it. It is impossible to over-rate his influence on the moral, social and political life of his fellow-countrymen, and that influence, though possibly on the wane now, has extended over 2,000 years. The cult of Confucianism, as practised in modern times, did not, however, become fully established until many centuries after the Sage's death. He is not worshipped

as a god, but sacrifices were officially offered to his manes by the Emperor, in the name of the State, and in numerous temples throughout the country, by officials. The cult, however, does not appeal to the masses, the temple obser- vances being confined to the official classes and the literati. At the same time, Confucian ideals of life and conduct permeate the whole people.

TAOISM. Taoism is, theoretically, the development of a philosophy the doctrine of the right way, the "return " to which represents the consummation of supreme happiness— enunciated by, or rather attributed to, Lao-tzu (flor. 570 B.C.). As practised to-day in China, Taoism is a debased ritual, embodying a polytheistic hotchpotch of witchcraft and demonology. On the subject of Taoism Mr. R. F. Johnston says:-

•

Most of the Taoist temples (in the territory of Weihaiwei) are poor in outward appearance, and their interiors are often dirty and evil-smelling; while the images of the numerous Taoist deities are of cheap manufacture and tawdry in ornament. . . It is only the larger temples that have resident priests.

The official duties of the priests consist in very little more than looking after the temple buildings, seeing to the repair of the images when their clay arms and legs fall off (this is a duty they often shirk), and calling the attention of the deities to the presence of visitors who have brought offerings and desire to offer up their prayers. Their services as magicians and retailers of charms are also invoked from time to time by private persons. Apart from these (occasional) visits the temples are usually deserted except on one or two annual occasions, such as the celebration of a local festival.

Popular Taoism provides deities or spiritual patrons for all the forces of nature, diseases (from devil-possession to toothache), wealth and rank and happiness, old age, death, childbirth, towns and villages, trades, (B307/177)x

B 2

war,

•

Chap. III.-Religions.

20

mountains, rivers, seas, lakes and canals, heaven and hell, sun, moon and stars, roads and places where there are no roads, thunder, every separate part and organ of the human body, and, indeed, for almost everything that is cognizable by the senses and a good deal that is not. It need hardly be said that no Taoist temple in existence contains images of all these spiritual personages, or a hundredth part of them. Each locality possesses its own favourites."

BUDDHISM.-Buddhism in China proper, where it was introduced from India during the first century of our era, bears as little resemblance to the religion in its purer forms, such as may be found in other countries, as does modern Taoism to the presumptive doctrines of Lao-tzu, If Buddhism exists anywhere in the country as a pure faith, it will be only in some of the great monasteries, and even in these the monk- hood is almost entirely a degenerate class. As a so-called religion of the people it is hardly distinguishable from Taoism, whose deities it has had to borrow largely, in order to popularize its own temples. Its hold on the people is restricted mainly to beliefs and ceremonies connected with death and burial.

The Dalai Lama is the supreme pontiff of Buddhism, the spiritual and temporal ruler of the greater part of Tibet.

MOHAMMEDANISM.-It is estimated that Mohammedanism is the religion of from fifteen to twenty millions of people in China. They are to be found mainly in Chinese Turkestan, Kansu, Shensi and Yunnan. Although

Although no disabilities are placed upon Mohammedans for their religion, they are marked off from their fellow-countrymen almost as distinctly as if they were of a separate nationality. Individual Moham- medans, however, rise to prominence in Chinese officialdom. It is a debated point to what extent Chinese Moham- medanism conforms to the tenets of Islam otherwise than in abstinence from pork; but, as one observer remarks, the fact remains that some Chinese Mohammedans do still occa- sionally make the pilgrimage to Mecca and well-attended Mohammedan mosques may yet be found in at least half the provinces of China."

CHRISTIANITY.-Christianity, as far as can be established by records, was first introduced into China by the Nestorian priest Alopen in A.D. 635. The Nestorian church was flourishing in the fourteenth century, but at the end of the sixteenth there seems to have been no trace and no memory of it. In the latter part of the thirteenth century China was visited by Roman Catholic missionaries.

The closing of the overland route to China led to a break in missionary endeavours to reach the country until the sea route had become better

better known. St. Francis Xavier

21

Chap. III.-Languages and Interpreters.

attempted to reach China, but died in 1552 at an island off the coast of Kuang-tung. From that date, however, China has been visited by a constant stream of Roman Catholic missionaries, particularly Jesuits. Their scientific knowledge has won them the favour and esteem of the Chinese.

The Roman Catholic Church is to-day represented in all parts of China: it has 50 bishoprics, and there are over 1,300 foreign missionaries.

The history of Protestant Missions in China begins with the arrival in Canton of Robert Morrison in 1807.

Until 1860 only a few ports were open to foreign trade and residence, but the Treaty of Tientsin made the wide regions of the north accessible to foreign trade and travel, and the missionaries took full advantage of it.

The manner in which so many of their fellow-countrymen faced their death in the Boxer Rising, and the immediate rising again of the mission churches amid the ruins wrought in the persecution, opened the eyes of the Chinese and awakened thought. From this time forward the Christian message gained a new and wider hearing in every department of mission work there has been steady advance, and accessions to the churches have been year by year increasingly numerous, To-day there are at work some 18,000 Protestant Missionaries and Chinese Evangelists; there are full communicants to the number of 350,000, and a Protestant Christian community in China of some 700,000 people.

3. Languages and Interpreters

The Chinese language may be divided as follows:-

(a) The ancient style, in which the classics are written; sententious, abbreviated, vague, and often unin- telligible without explanation.

(b) The literary style, less abbreviated and, therefore, more intelligible; it might be described as poetry written in prose on account of a rhythmus, as it is termed, in which it is written. The essays written by candidates are composed in this style, as are also official proclamations.

(c) The business style, which is plain enough to be intelligible; it is prose without the poetry element, and is in general use for commercial purposes, legal documents, official and business correspon- dence. Governmental, statistical and legal works are written in it.

(d) The colloquial, or spoken languages, which are divided into numerous dialects referred to below.

Chap. III.-Languages and Interpreters.

22

There are scarcely any books written in them in South China, and yet it is impossible to speak in any other language, and to the great majority of the poorer classes no other is intelligible in its entirety.

The difference between the book style and the colloquial might be likened to the difference between an ordinary English book and some highly scientific or technical work so bristling with scientific terms, technical expressions, or mathematical formula that it would be nearly incomprehensible except to one who had been specially educated for years, making such subject a speciality.

The Chinese language is very rich in nature sounds, vocal gestures, and tones, while the interjectional element appears to have had its full share in the formation of some portion of the language.

Many of the words and terms in use in the Southern Provinces are imitative of sounds in nature, of noises of falling objects, of calls and cries of animals, birds and insects, and of actions by man himself.

It may be remarked here that Englishmen are supposed to acquire Chinese with greater ease than any other Europeans, a fact which may prove an inducement to officers and others stationed in the Far East to commence learning the language of a country which appears likely in the near future to play so important a part in the destinies of the civilized world.

To appreciate the number of different dialects spoken in the various districts of China, it is necessary to realize the huge size and population of the Republic and the great antiquity of the Chinese race. The distinguished Terrien de Lacouperie produces incontestable proofs to show that the Chinese originally migrated from some point in Mesopotamia, south of the Caspian Sea, and fixes the period as being about 4,000 years ago. Chinese writers, however, assert that their legendary history began at a date calculated at 2852 B.C. to 3322 B.C. The Chinese formed their settlements in the upper valley of the Yellow River, and after pushing eastward to the sea, spread northwards and southwards as the population multiplied and increased, and absorbed or destroyed the aborigines. It is only natural, then, that with the lapse of years the manner of speech should be totally different in the various parts of the country, which may be said to fall into three grand divisions : the dry North, the Yang-tze belt, and the Southern Provinces.

The people of the north speak a clean-sounding dialect, Mandarin (called, in Chinese, Kuan-hua), which is the official language of the Republic; in the Yang-tzu belt the speech,

23

Chap. III.-Languages and Interpreters.

which is clear and distinct in the north, becomes more slurred and soft; it is still the official or Mandarin dialect, but each mile farther south you go the harsh gutteral tends to disappear and be replaced by the softer labial. Around the basin of the Yang-tze the gutturals have entirely disappeared and the Che-Kiang Chinese are even laughed at by everybody else as having women's voices.

It will thus be recognized that Mandarin, or variations of it, is understood throughout the Northern and Central Pro- vinces; passing, however, to Southern China, where the inhabitants are but half Chinese in their origin, a traveller is dismayed at the dialects spoken in Kuang-tung, Kuang-hsi, Kuei-chou, and Fukien, for each is an entirely different language from the other and quite distinct from Mandarin ; in fact, few Chinese, excepting the natives of the province, can acquire the dialects of the region, and there is no Chinese but will hold up his hands in horror when you mention this bird-chattering language, but Mandarin, or a variation of it, is, however, understood in Yun-nan, the fifth Province of Southern China.

Cantonese is somewhat akin to the ancient language of China (spoken about 3,000 years ago), while the Hak-ka also contains traces of a high antiquity; in fact, it may be said that all the languages spoken in the south-east of China have traces of the ancient speech.

After the division of dialects proper, of which there are about eight, there are the lesser divisions of sub-dialects and local patois, and it is quite a fallacy to believe that a man who knows one of the dialects, such, for instance, as Cantonese, is then a perfect master of all that may be said by people speaking that language. The real facts of the case will be better understood if one instances the bewilderment of a cockney when stranded amongst a crowd of Yorkshiremen speaking the Yorkshire dialect in its broadest.

Mandarin, as the official dialect, is most widespread; almost all high officials require a knowledge of Mandarin, and those who do not already know it, generally have to learn it. The other languages of China are spoken by smaller populations. but the numbers are still large enough to command respect. Thus 20,000,000 Chinese speak Cantonese in some form or another, and this language is in use throughout the larger part of the Kuang-tung Province, while about one-third of the people of this province speak Hak-ka; in the north-east of the same province there is also a considerable population speaking the Swatow dialect and its variations.

Many of the Chinese in the neighbourhood of Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports have evinced a great desire to learn

Chap. III.-Education.

24

English, as the Chinese are shrewd enough to see that the potentialities of wealth are present in a knowledge of the foreigners' tongue. Of late years this desire has spread, and the Chinese Government itself has taken the movement under its fostering care, and as long ago even as 1896 instructions were issued to the various Viceroys and Governors throughout the Chinese Empire to establish schools for the teaching of the English language, while schools under British Government control have long been established for the same purpose in Hong Kong.

"

The most common means of intercourse between Europeans and Chinese in Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports is Pidgin- English." This mongrel talk is a literal translation of a Chinese sentence into English words, or the Chinese idea of such, for their pronunciation is defective and the letter "r" is dropped and "1" substituted. A few of the words employed are, however, Chinese, so distorted as to be almost past recognition, while Portuguese, Malay, and Indian have also added a few words to the vocabulary; the result is a wonderful gibberish which new-comers often find it useful to learn.

For various reasons there is practically nobody now serving in the British Army with a useful knowledge of Cantonese, or any of the dialects spoken in South China.

There are, however, a number of good interpreters of British race to be found among Hong Kong Government civil servants, missionaries, and merchants, from which any military require- ments can be satisfied. In addition, a large number of Chinese have a good knowledge of English.

4. Education

The most important schools are Queen's College and the Ellis Kadoorie School, at which, though the majority of the pupils are Chinese, some Indians, and a few Japanese attend; the Belilios Public School for Chinese girls, and a Government school for Indians at Soo-kum-poo.

Central School and Kowloon Junior and Victoria schools for children of British parentage have an average attendance of 204. There is also a school for the children of the Peak district with an average attendance of 45. The Diocesan School and Orphanage and St. Joseph's College are important boys' schools in receipt of an annual grant. The Italian, French, and St. Mary's Convents, and the Diocesan Girls' School are the most important of the English schools for girls.

The Hong Kong Technical Institute affords an opportunity for higher education of students who have left school.

The University of Hong Kong, incorporated under the

25

Chap. III.-Labour.

local University Ordinance, 1911, and opened in 1912, is a residential university for students of both sexes for the promotion of arts, science and learning, the provision of higher education, and the development and formation of the character of students of all races, nationalities and creeds.

The University includes the three Faculties of Medicine, Engineering and Art. Admission to all faculties is condi- tional upon passing the matriculation examination of the University or some examination recognized as equivalent thereto.

5. Labour available in different districts ;

normal

wages; how best obtained and organized; availability outside its own district; types of tools used.

In normal times there is an ample supply of labour to meet all requirements. The big engineering and shipbuilding firms employ large numbers of skilled men, and coolie labour (both male and female) is available in large quantities.

AVERAGE RATE OF WAGES FOR LABOUR, 1929.

Domestic servants ..

Gardeners

Labourers

Blacksmiths and fitters Carpenters and joiners Masons and bricklayers Painters

•

•

$15 to $40 a month. $12 to $25 a month. 50 c. to 75 c. a day. $1 to $2.50 a day.

$1 to $1.75 a day.

$1 to $1.50 a day.

30 c. to 75 c. a day.

Domestic servants expect only lodging in addition to their pay, but in some cases it may be necessary to provide board for artisans and labourers.

Chinese contractors and employers obtain labour at from 25 to 50 per cent. less wages than the above.

The present tendency is for all wages to go up to meet the increased cost of living.

The majority of big firms obtain their labour through Chinese compradors, who are responsible for supplying all labour required and for issuing pay. Coolies are generally organized in gangs of 20 with a headman for each gang. As most of the labourers come from Canton it can be said that labour is generally available for use in any part of the Colony. Skilled men use the same tools as Europeans. Transport has hitherto been generally effected by coolies carrying baskets slung over their shoulders by means of bamboo poles, but more modern methods are being introduced to meet the rising cost of labour.

Chap. III.-Attitude towards Foreigners.

6. Attitude towards foreigners

26

CHINESE. The proximity of Canton, which for centuries past has been a turbulent city and whose inhabitants are easily swayed by anti-foreign propaganda, must always be considered a factor in any estimate of the true sentiments of the Chinese population of Hong Kong towards Europeans.

A generation or so ago the normal attitude of the Chinese mind, official and unofficial, was one of condescension towards, not to say contempt for, or even hatred of, a people utterly different from themselves in language, dress, habits and customs.

In recent years, however, a closer and wider contact between Chinese and Europeans has brought certain facts to the attention of both, which show that this attitude can no longer be reasonably maintained, and it has been considerably modified, though by no means abandoned. Among the better classes on both sides there is a real appreciation of the good qualities of each other.

Of the peasantry, which composes by far the greater portion of the population of China, it may be said that they possess the good qualities almost always to be found among their class all over the world. In normal times and under normal conditions they show marked courtesy and consideration towards foreigners.

All Chinese appear, however, to be exceptionally susceptible to intimidation, and when subjected to it are liable to act in a manner which makes their friends despair of their ever reaching a level higher than that on which they at present exist. Unfortunately, there is a small but vociferous class in China which frequently exerts itself to work on this failing of its countrymen. This class is largely composed of those who have been educated abroad, and have returned with a grossly inflated idea of their own importance. They are consequently discontented, and as there is no market for the qualifications which they have acquired abroad, they are apt to turn, as they do in other countries besides China, to agitation and intrigue. The average Chinese, when worked on by such people, seems almost to go mad, and to strike against any foreign interests or persons within his reach.

As a rule, however, the attitude of the poorer classes is one of complete indifference to all that does not immediately concern them, and it is only by acting on their easily aroused apprehensions that they can be moved from their apathy.

During the past few years the whole of China has been in the hands of leaders who have impoverished the country by a series of fruitless civil wars. The student class has attributed much of the resulting misery to the foreigner, and has stirred

27

Chap. III.-Diet.

up a strong anti-foreign feeling. When the strike of the Chinese in Hong Kong started in June, 1925, à large pro- portion of the strikers who had originally migrated from the main-land went back to Canton, but they soon returned to Hong Kong. There is little doubt that a large number of the strikers were really unwilling to strike, but were intimi- dated into doing so by threats that their relations in Canton would be victimized if they remained at work.

The Chinese who remained in Hong Kong were orderly and easily controlled. Judging by the experience gained from the strikes of 1922 and 1925, it is thought that the attitude of the Chinese in Hong Kong during any emergency would be one of passive neutrality on the part of the majority, while only a small proportion would be actively friendly or hostile. Riots on a large scale are not anticipated, and it is thought that order could always be maintained by the existing police with small detachments of military in reserve.

PORTUGUESE.-It may be assumed that the Portuguese would be actively friendly in any emergency in the future, as they have been in the past.

7. Diet

Rice is the staple article of diet.

The following diet for a Chinese male prisoner sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour gives an idea of the food required by a Chinese workman to keep him in good condition :-

Rice.. Vegetables Chutney Oil Salt

Tea

•

Congee (rice gruel)

Rice..

Fresh fish

Chutney

Oil

Salt

Tea

•

+

•

8. Foreign residents

•

•

•

11 oz.

11 oz.

2 oz.

Breakfast.

•

1 oz.

•

•

ΟΖ.

Oz.

1 pint 12 oz.

11.0 a.m.

2 oz.

ΟΖ.

Supper.

OZ.

OZ.

Oz.

The number of foreigners in the Colony has been shown in statistics given at the beginning of this chapter. The most

བསམ་*

Chap. III.-Foreign Residents.

28

numerous non-British foreigners are the Portuguese, who are mainly engaged in trade.

The following nations have consular representatives in the Colony :-

General acts as Consul-

Belgium.

(French Consul-

Mexico.

Netherlands.

General for Belgium.)

Nicaragua.

Bolivia.

Brazil.

Norway. Panama.

Chili.

Denmark.

France.

Guatemala.

Italy.

Japan

Peru.

Portugal.

Siam. Spain. Sweden.

U.S.A.

29

Chap. IV. General Description.

CHAPTER IV.

POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY

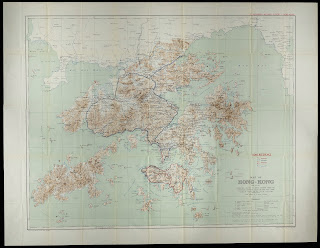

1. General description (See Map G.S.G.S. No. 1393B)

Hong Kong is the naval base and headquarters of His Majesty's ships on the China Station, and is the only Imperial coaling station for the British Navy east of Singapore.

The colony has attained very great commercial importance and prosperity by reason of its favourable geographical position, unequalled steamship communications, excellent harbour facilities, and the proximity and ready accessibility of the populous Canton river delta.

The total area of the colony is 410 square miles, of which the main-land contains 286, Hong Kong Island 29, and the other islands the remainder. About one-sixth of the whole area is flat and highly cultivated land; the remainder is mountainous and unproductive.

2. Frontiers

The boundaries of the colony are shown on the map. They extend up to high water mark on the Chinese territory bounding Mirs and Deep Bays,

On the main-land the frontier is clearly marked for the greater part of its length by the Sham-chun River.

It should be noted that the line which separates Kowloon from New Kowloon also divides territory ceded to Great Britain from that which is only leased to her for a period of 99 years from 1898.

3. Principal Towns

For the purposes of this Report, the towns of Victoria and Kowloon, though divided by the harbour, may be con- sidered as one, and the following particulars apply to them taken jointly :—

(a) Population--about 750,000.

(b) The type of house varies from Chinese to European.

Chap. IV.-Principal Towns.

30

The lay-out and streets

and streets are modern, and a great deal of billeting accommodation could be found.

(c) The towns are administered by the government, which constitutes the only executive municipal authority.

(d) The principal government buildings and all foreign consulates are in Victoria, which is also the commercial centre of the Colony.

(e) Several government and other hospitals are located in both towns.

The Military Hospital, Hong Kong, a three-story brick building, occupies one of the very best situations in Victoria. It is on an elevation of about 500 feet, over- looking the harbour and is open to all sea breezes. It has accommodation for 100 beds, including 12 for officers. The hospital contains the usual modern operating theatre, X-ray department, and pathological laboratory. Quarters for nursing sisters, R.A.M.C. personnel and their families are provided close to the hospital. There is no military families hospital in Hong Kong, women and children requiring admission to hospital being sent to the Civil General Hospital (for medical and surgical complaints); maternity cases are sent to the Victoria Hospital.

A military hospital of 100 beds for native troops is situated at Kowloon; it consists of a number of brick buildings on the bungalow plan; it also is well equipped on modern lines.

Mount Austin Barracks, situated on the Peak, is the only so-called sanatorium for the troops. It has accom- modation for two companies and about six married families. As these barracks form a part of the regular accommodation for the British infantry in Hong Kong, their use as a sanatorium is limited. However, arrange- ments are made for the changing of companies from time to time from the Lower Level to the Peak. Convalescent soldiers are sent to Mount Austin on discharge from hospital after a protracted illness. A military sanatorium used to exist at Magazine Gap, about 1,000 feet above sea level. It was destroyed by a typhoon in 1923 and has not since been rebuilt. It was used to accommodate a company of Royal Artillery at a time.

The Naval Hospital is a well-equipped modern hospital, where the sick from the Royal Navy at Hong Kong are treated. It has a staff of three medical officers and three nursing sisters, all of whom are accommodated in the hospital grounds.

The hospitals supported by the Colonial Government

31

Chap. IV. Principal Towns.

are the Government Civil Hospital, the Victoria Hospital for women and children, the Kowloon Hospital, the Lunatic Asylum, and the Kennedy Town Hospital. Patients are admitted to these institutions on payment of 8, 5, or 2 dollars per diem, according to the class of ward. There are also free beds. Both Europeans and Asiatics are admitted. The Government Civil Hospital provides 196 beds in 23 wards. There are 5 maternity wards providing 16 beds. The Victoria Hospital for women and children is situated on the Peak, and provides 41 beds. This institution is being enlarged by the addition of a maternity block containing 20 beds. The Kowloon Hospital provides 48 beds in 11 wards. The Lunatic Asylum provides accommodation for 40 patients.

Kennedy Town Hospital is reserved for infectious diseases, but is rarely used for cases other than smallpox. It provides 26 beds.

The Peak Hospital, formerly a private institution owned by a firm of doctors, is now a Government institu- tion, but is still run as a nursing home. The fees charged are 10 and 5 dollars per diem, according to ward.

The Alice Memorial and Nethersole Hospitals are partially endowed missionary institutions for treatment of Chinese.

The Sharp Memorial Hospital is an endowed institu- tion, situated on the Peak, for the treatment of Europeans who cannot afford to pay large fees.

The Tung Wah Hospital is a Chinese philanthropic institution for the native sick. The patients have the option of Chinese or English treatment. An English Government doctor inspects it periodically.

A matron, 3 assistant matrons, and 35 Eurpoean nursing sisters are employed in the Government hospitals, and two are provided for outside nursing. Chinese girls are trained as nurses at the Government Civil Hospital. There is also a well-equipped Bacteriological Institute and an Analytical Laboratory.

(f) Banks.-As an important centre, Hong Kong has many banks; some of the most important are :—

i. The Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation; ii. The Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China; iii. The Mercantile Bank of India ;

iv. The International Bank;

but there are many others. All are located in Victoria.

Chap. IV. Principal Towns.

32.

(g) Engineering works of all kinds are situated in both towns. Dockyards constitute the most important of these.

(h) Electric power for the Island is provided from a station at North Point, and for Kowloon by one at Hunghom. The former generates 5,000 and the latter 3,500 kilowatts.

(i) Victoria has an electric tramway system extending along the north of the Island, with a total length of about 10 miles. It operates 54 cars, each carrying 50 passengers.

(j) The principal sources of water supply for Victoria are the Tai-tam reservoirs, and for Kowloon, the Kowloon and Shek-li-pui reservoirs. These provide a supply sufficient for all ordinary present needs. There are also reservoirs at Pok- fu-lum and Aberdeen.

Increasing population having led to the imposition of restrictions in years when rainfall is below the average, extensive new sources of supply are being developed in the Shing Mun Valley.

Both in Hong Kong and Kowloon all public water supplies are from upland surfaces, and purification is by sedimentation, sand filtration and chlorination. The water is soft and of excellent quality.

(k) A water-carried sewage system has to some extent replaced earth closets. Where the latter are in use the excreta are removed by coolies and sold to Chinese contractors for agricultural purposes.

During abnormally dry seasons only an intermittent water supply can be provided. This leads to storage of water in all sorts of receptacles and to the irregular and indifferent flushing of water closets, with the attendant sanitary evils. This matter is receiving the very particular attention of the Colonial Government at the present time, and it is hoped that when the scheme for increased water supplies on the Island and at Kowloon have been completed these evils will disappear.

Storm water, which in Hong Kong suddenly increases to enormous volume, is carried off by a separate system of drains. By this means disastrous flooding of sewers is avoided.

(7) Hong Kong has a well-managed dairy farm and cold storage company. This company supplies fresh milk, eggs, poultry, fresh and chilled meat, vegetables and fruit in large quantities, both to the ships using the harbour and "to the public. The supplies are of the highest quality and the plant is of the best modern type. With this exception the towns draw almost all their supplies of every sort from overseas, except for fish. The Colony produces little more than will support its rural population.

33

4. Description of Port.

Chap. IV. Description of Port.

Hong Kong is a port which handles yearly a tonnage equal to that of the greatest ports in the world. It is equipped on a scale comparable to that of Liverpool or Southampton.

(a) CONTROL OF THE PORT.—A Harbourmaster's department, working under the Government, controls the Harbour, the limits of which are shown on the map.

(b) LANDING FACILITIES.-Personnel, animals, and stores could be landed and moved to their destinations without difficulty.

(c) LABOUR SUPPLY.-Many thousands of Chinese dock labourers are normally available. They work up to 12 hours a day for a wage equal to about 1s. 6d. They are usually reliable, but are easily intimidated by agitators of their own race, and have at times struck work for long periods. The possibility of their doing so, for reasons which cannot be foreseen, must always be borne in mind.

(d) CARGO HANDLING APPLIANCES.-Most of the cargo arriving in the Port is handled by the lifting apparatus of the ships which carry it. There exist, however, in the naval and commercial dockyards fixed and travelling cranes of all kinds with lifting capacities up to 150 tons.

(e) TRANSIT ACCOMMODATION.-Ample transit accommoda- tion for goods is available for any possible military require-

ments.

(f) ROAD AND RAIL COMMUNICATIONS.--For road and rail communications from the Port, see map. Assembly places for troops could be found on the Island, at Happy Valley, and on the Mainland, at King's Park.

(g) AVERAGE AMOUNT OF COAL AND OTHER FUEL, AND OWNERSHIP. At ordinary times from 60,000 to 100,000 tons of coal is stocked in Hong Kong. This is in the hands of various owners, of whom the principal is the Kailan Mining Administration. It is located at various points on the water front, both on the Island and on the mainland. For domestic purposes wood is largely used by the Chinese. This mostly comes down the West River, and stocks amounting to about 2,000 tons are usually held in Hong Kong.

(h) SITUATION AND LOCATION OF OIL TANKS.-The principal stocks of oil in Hong Kong are those held by the Asiatic Petroleum Company, the Standard Oil Company of New York, and the Royal Navy.

The Asiatic Petroleum Company has tanks holding in all 53,000 tons, of which 36,500 tons are held at North Point in nine tanks of capacity varying from 8,000 to 500 tons, and 16,500 at Tai-kok-tsui in seven tanks varying from 4,000 to 1,500 tons.

(B 307/177)X

C

Chap. IV.-Description of Port.

34

The principal depot of the Standard Oil Company is at Lai-chi-kok, where there are 13 tanks, each holding about 7,000 tons.

The Naval oil tanks, of which there are 4 with a total capacity of 26,000 tons, are near Yau-ma-ti.

In addition to the foregoing, the Vacuum Oil Company holds stocks of lubricating oil, mostly in cases, and the Texas Company also has an establishment.

(i) DETAILS OF DOCKYARD, &c., ACCOMMODATION available at the Port are as follows.

Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company, Kaulung Docks,

Hunghom (1).

Length.

Breadth.

Depth of water over sill at ordinary spring tides.

No. 1 Dock (Admiralty)

700 ft.

86 ft. at en- trance at top 70 ft. at en- at

30 ft.

18 ft. 6 in.

371 ft. on keel

blocks

264 ft. on keel

blocks

No. 2 Dock

No. 3 Dock

Patent

No. 1 Patent

No. 2

Slip

Slip

230 ft. on keel

blocks

240 ft. on keel

blocks

trance bottom

74 ft. at en-

trance

49 ft. 3 in. at

entrance

60 ft. at en-

trance

60 ft. at en-

trance

14 ft.

14 ft. depth on

blocks. 12 ft. depth on

blocks.

The approaches to the docks are perfectly safe, and the immediate vicinity affords capital anchorage. The docks are substantially built throughout with granite. Powerful lifting shears with steam purchase stand on a solid granite sea-wall, alongside which vessels can lie and take in or out boilers, guns, &c. Capacity of shears, 70 tons. Depth of water alongside at low tide, 24 feet. There is good access to the docks by road.

All up-to-date engineering appliances are available, and steamers up to 700 feet in length can be built. There is a length of 1,000 feet of wharfage in Hunghom Bay, with a depth alongside of 5 feet to 45 feet, and steam shears of 100 and 15 tons,

Kowloon Marino (2).-Reclamation works are still in

35

Chap. IV.-Description of Port.

progress here, and there is every likelihood that the biggest developments for the provision of wharves and docks will take place here. There is good access to the railway. The area at present available forms an excellent site for the forming up of troops.

Holt's Wharf (3).—Can berth two ships with a draught of 25 feet at L.W.O.S.T. Four steam cranes available. Barrier for sheltering lighters. Good transit sheds and warehouse accommodation. Direct access to road and rail. Direct access to assembly ground at (2)

Hong Kong and Kowloon Wharf and Godown Co.'s Piers (4).-Capacity for berthing ships :-

Maximum draught of vessels which may berth alongside at L.W.O.S.T. :-

Number of ships which may berth simultaneously..

25 feet

28 feet

30 feet

22221

32 feet

Steam cranes on rails can go alongside any ship. There are extensive transit sheds and warehouses. No direct access to rail. There is a good road running at the back of the transit sheds.

Man-of-War Anchorage (5).-Torpedo depot and coal sheds. Oil store for the Navy. Vessels of 20 feet draught can lie alongside the western side of the jetty at the coaling camber by placing lighters of 20 feet beam between them and the wall.

Yau-ma-ti Shelter (6).—This is a typhoon shelter for junks and small craft.

Asiatic Petroleum Company's Wharf (7).-Pipe lines laid to the jetty for bunkering ships. Depth alongside, 21 feet.

Cosmopolitan Dock (8).-Length on keel blocks, 466 feet; breadth at entrance, 85 feet 6 inches. Depth of water on sill at ordinary spring tides, 20 feet. There is 550 feet of wharfage alongside, with depths of 8 to 15 feet, deepening rapidly off, and there are steam shears of 20 tons. The approaches to the docks are safe, and there is good anchorage in the vicinity.

Standard Oil Company's Wharf (9).—There are no arrange- ments here for bunkering ships.

Standard Oil Company's Wharf (10).—There are no arrange- ments here for bunkering ships.

China Merchants' Pier and Jardine's Wharf (11).—Maximum

(B 307/177)X

C⚫

C 2

Chap. IV. Description of Port.

36

draught of vessels which may berth alongside at L.W.O.S.T., 23 feet. Number of vessels which may berth simultane- ously, 3.

Between (10) and (11) there are many go-downs, but no accommodation for berthing large vessels.

Douglas Pier Central (12).-Maximum draught of vessels which may berth alongside at L.W.O.S.T., 26 feet. Number of vessels which may berth simultaneously, 2. No cranes are available and no warehouses.

Between (11) and (12) a large passenger and cargo trade with riverine ports is carried on.

The whole of the area behind the sea-front between (10) and (12) is very crowded and the facilities for moving troops and stores in this neighbourhood are not good.

Naval Dockyard (13).-This contains a dry dock 490 feet long, and has berths available to take two ships on the outer wall with a draught of 28 feet. It is the most suitable place for the disembarkation of troops and guns on Hong Kong Island.

Causeway Bay Shelter (14).-Typhoon shelter for junks and small craft.

Asiatic Petroleum Wharf (15).—Berthing available here for one oil tanker to discharge, and ships up to a draught of 24 feet to bunker.

GENERAL REMARKS.-The majority of vessels are coaled from lighters. The berthing accommodation is at present very limited.

limited. The majority of big ships load from and unload into lighters. Very extensive harbour development has been planned. The greatest developments will probably take place in Hunghom Bay. (For details, see Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce Report for 1924.).

LABOUR.-Dock labourers are all Chinese. As explained in Chapter III, the population of Hong Kong is a migratory one and it is impossible to say how many labourers would be available in any emergency.

In normal times there is ample labour to meet all demands.

OUTSIDE THE LIMITS OF HONG KONG HARBOUR. Tai-koo Docks. (16)-The main dock has been built to Admiralty requirements.. The dimensions are 787 feet extreme length-750 feet on the blocks-120 feet wide at the coping-77 feet wide at the bottom-88 feet width of entrance at the top-82 feet width of entrance at bottom- 34 feet 6 inches over centre of sill at high water spring tides- 31 feet depth over sides of sill at high water spring tides. The dock has been designed to permit of further increase in

37

Chap. IV. Description of Port.

its length if it should become necessary. It can be filled in 45 minutes and pumped out in 2 hours 40 minutes.

There are also three slipways.

Number 1

Numbers 2 and 3

Length. 1030 feet.

Width.

80 feet.

9931 feet.

60 feet.

No. 1 ..

Nos. 2 and 3

Length.

Steamers that can be taken.

Draught.

Displacement.

325 feet. 18 feet.

3000 tons.

300 feet. 17 feet.

2000 tons.

The building yard is 550 feet long and 500 feet wide, and has been equipped to construct torpedo boat destroyers and all sorts of passenger and cargo steamers.

The engine-shops are extensive and complete. They are capable of undertaking the building of all classes of steam engines, including geared turbines. The chief motive power is electricity generated by gas engines, the gas producing plant being the largest installed in the Far East.